Written - February 2022

The Legacy Problem

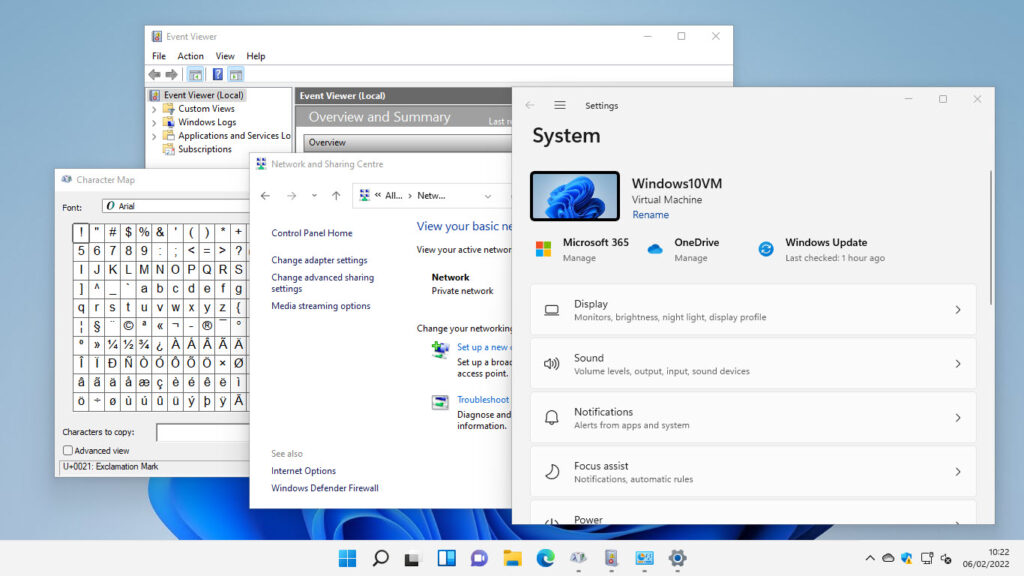

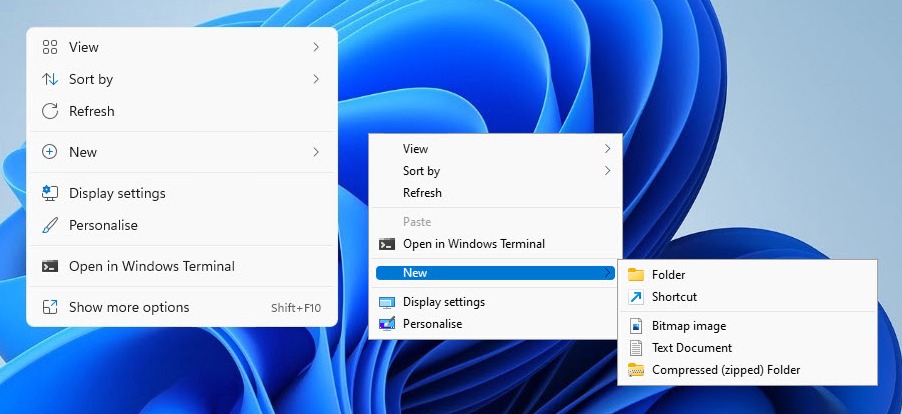

Every time a new version of Microsoft Windows is released, Microsoft add new and ever prettier interface items. Windows 11 brought with it the new Start Menu and the semi-transparent acrylic design the company calls “fluent”. You don’t have to dig very far however to find older interface items that, in some cases, date all the way back to Windows NT and Windows 95, almost thirty years ago, and which have never been updated.

It’s a similar story with context menus, some of which also date back to the earliest days of Windows. Some observers, especially this one, find this immensely frustrating. Okay, so the average non-technical home or office user will probably never even see this stuff, but for “power users” as they’re often termed, and IT Pros, these legacy interfaces will be something we see often, if not even every day.

This is my biggest single personal bugbear about Windows whenever a new version is released, but I have been doing some digging into why this situation is as it is, and I have developed a certain understanding for the task Microsoft would have to take on to update all of these older interfaces.

The cause of the ongoing use of legacy interfaces in Windows stems from three problems. The first is that programming languages have changed and developed over time. Remember that Microsoft Windows is a piece of software like any other, admittedly a very large and very complex piece of software. Some of these older legacy interfaces were written in languages such as C++ that aren’t used in modern Windows development. This means that updating them would require a complete from-scratch rewrite.

The second problem is that many of the people that wrote these parts of Windows have long since moved on from the company, and for some of these components it can difficult for the current developers at Microsoft to know how they work, that’s even if they have access to all the original code.

The third problem is business and corporate users. These are hugely important customers for Windows and they demand conformity with their systems and procedures. Changing too much requires extensive retraining of staff, and probably purchasing of additional software, all of which is expensive and time-consuming. For as flexible as many corporations can be, when it comes to rolling out new IT systems they can be horrendously behind everybody else.

Microsoft are, very slowly and steadily, rolling these older interfaces, primarily Control Panel applets at the moment, into Windows Settings. This means these older interfaces are going to disappear eventually, but it’s going to be many, many more years yet before it happens.

The Virtualised OS

Back in 2019, Microsoft announced two new devices, Surface Duo and Surface Neo. These were designed to run a new version of Windows 10, called Windows 10X. This new version of the operating system would be a huge leap forward for Windows and include some highly important new technologies.

The first is that the entire operating system, and every installed app and program would be virtualised in a container. What this means is that instead of the operating system and software sitting in a shared space, with each making direct calls to the processor and hardware, they would instead sit inside separated instances of the Windows core. Also called the kernel, this is the underlying part of Windows that does all the work, and which your interface sits atop.

The reason for this is that nothing on the PC would be able to interact with anything else on the PC at a low level, with all interactions such as cross copy and paste being handled within their own containerised environment.

The upshot of all this is that Windows would suddenly become much more robust and stable, and considerably more secure. If malware infected an app or a file, it would be near impossible for that malware to also infect the core OS or any other apps or files. Also if a component crashed it wouldn’t bring everything else down with it, it would just quietly restart on its own.

Perhaps the part most visible to PC users would be that Windows Updates would under this system only very rarely require a restart of the PC, with just the relevant parts of the OS being restarted in their virtualised containers while the desktop experience continued in the foreground, uninterrupted.

Only one of these two devices ever saw the light of day, the Surface Duo, and when it was eventually released Microsoft had scrapped Windows 10X, folded its new interface components into what would become Windows 11, and released the Duo with Google’s Android operating system instead.

Sadly, Microsoft couldn’t get this technology to work reliably. Reportedly it was slow. This doesn’t mean Microsoft have given up on the idea however and we can fully expect this new technology to feature heavily in a future version of Windows. This means that finally all of the older legacy code that’s been sitting in the operating system since the days of Windows 95, and in some cases even longer, can finally be stripped away. That would take all of the vulnerabilities and stability issues of that code with it and, essentially put me out of a job as there’d be no more need for Windows troubleshooting books and courses. Go on Microsoft, put me out of a job, I’m coming up to retirement anyway and I’d absolutely love it!

Your PC in the Cloud

Something else that will feature heavily in the future of Windows, and that Microsoft have already begun to make available, is what’s called Cloud PC. This is available through the company’s Windows 365 programme for corporate customers, though eventually it will inevitably roll out to be available to everybody that wants it.

Cloud PC uses virtualisation technologies in Microsoft’s Azure cloud services platform that have been around for a few years already to stream a Windows desktop to your computer. This has several advantages. Firstly it can be centrally managed in the cloud, so system administrators no longer have to maintain a whole fleet of desktop and laptop PCs.

The second benefit is that this Windows desktop can be run on absolutely any computer, from a Windows laptop to a Google Chromebook or an Apple iPad. The benefits with this are especially notable when it comes to home or remote workers. Home workers won’t need to have work apps and files installed on their own computer and they won’t need a Windows PC either. The work environment can be streamed to the user’s own computer, no matter what it is or where it is.

The third advantage is that people won’t need to have a powerful computer to perform powerful tasks. We’re all trying to become more sustainable and reduce our energy consumption. Part of this is moving to less powerful computers, and because all the processing for a Cloud PC takes place in a datacentre somewhere up in the ether, even a basic Chromebook can be used to edit and render video or perform computer aided design duties.

These are all things we can expect to see in future versions of Microsoft Windows. Maybe not in the next few years, it could take longer, but it’s highly likely that all of this will be the future of computing that we will all be using at home and at work into the next thirty years.